July 30, 2014

(Originally published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and can also be found also at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/pacnet-62-indonesia%E2%80%99s-john-adams-moment )

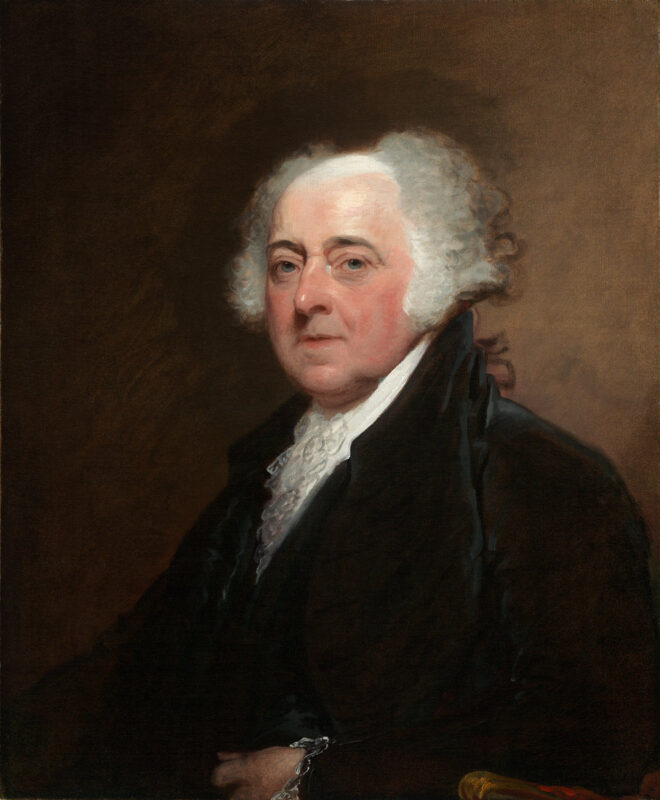

There was a moment of time in our own history, when our new democracy peaceably and orderly passed the reins of power from George Washington, at the end of his second term, to John Adams. It had never happened before in history. The “John Adams Moment” firmly established

the precedent  in the new, American democracy, of a Presidency limited to only 2 terms. That tradition lasted up until the time Franklin Roosevelt and was resumed thereafter by Constitutional Amendment. It was a transition moment when the country broke away peacefully from a military/civilian leader, Washington, to a purely civilian leader, John Adams. Our own “John Adams Moment” set the tone and the tradition for generations that followed. Indonesia, following its recent divisive election, is at a similar, “John Adams Moment” in the strengthening of its own new democracy. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), a military/civilian leader, will step down after his own 2nd term this coming October, and relinquish power to a new, duly- elected civilian President, Joko Widodo (Jokowi). This is a historic, critical step in the development of Indonesia’s own, young democratic traditions.

in the new, American democracy, of a Presidency limited to only 2 terms. That tradition lasted up until the time Franklin Roosevelt and was resumed thereafter by Constitutional Amendment. It was a transition moment when the country broke away peacefully from a military/civilian leader, Washington, to a purely civilian leader, John Adams. Our own “John Adams Moment” set the tone and the tradition for generations that followed. Indonesia, following its recent divisive election, is at a similar, “John Adams Moment” in the strengthening of its own new democracy. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), a military/civilian leader, will step down after his own 2nd term this coming October, and relinquish power to a new, duly- elected civilian President, Joko Widodo (Jokowi). This is a historic, critical step in the development of Indonesia’s own, young democratic traditions.

The Indonesian democracy has developed out of the dark, bloody days of rioting and violence in the wake of the collapse of the Thai baht and the Asian Financial crisis in 1997-98. The financial implosion of Indonesia’s rupiah occurred along with the dismantling of the autocratic and highly corrupt Suharto regime. Since that time, Indonesia has re-invented herself in a little over a decade and a half, repaired her devastated economy, and has now emerged as a robust democracy in Southeast Asia, with a plethora of newspapers, talk shows, media sources, and strong voter participation. It is impressive progress in less than two decades.

The recent Presidential election campaign was a hard-fought battle, but free of violence. And, although religion is never entirely absent from Islam’s foremost democracy, this was a contest fought overwhelmingly over secular issues.

Jokowi, represents a marked departure from Indonesia’s past. He started out as a small business owner, a humble furniture seller, and became a pragmatic, uncorrupt mayor. He is not from the usual clutch of political and business dynasties and their sleazy cronies. He represents something new for Indonesia. The 53-year-old is the first of a political generation reaching the national stage since popular protests in the late 1990s that toppled Suharto. Jokowi’s rise would have been inconceivable without the radical political decentralisation which is perhaps the outstanding success of Indonesia’s democratic journey. He began his political career as mayor of Solo, a medium-sized city in Java, the most populous island, before becoming an immensely popular Governor of Jakarta, the capital, in 2012. It is there that he forged a reputation for can-do competence and clean government that won the admiration of many and propelled him into the Presidential race.

Jokowi has a good record of dealing with the concerns of ordinary Indonesians: clogged traffic, poor sanitation and petty, bribe-taking bureaucrats. He is also more comfortable working with Christians or ethnic Chinese than most Indonesian politicians have been and are. Indeed, his opponents tried to turn his hostility to religious intolerance against him by claiming that he was in fact a Christian. Certainly, Jokowi is a new kind of Indonesian leader, but he is still a devout Muslim. In the three days before actual election in which Indonesian law forbids campaigning, Jokowi made a lightening pilgrimage to Mecca. But he also embraces religious pluralism. And, though no room exists on the Indonesian political spectrum for anything like economic liberalism, he is less of an economic nationalist than his opponent in the election, former Special Forces General, Prabowo Subianto, once Suharto’s son-in-law with a tainted human rights record, a throwback to Indonesia’s darker past.

Foreign investors are now pleased with the Jokowi victory. He understands the need to cut ruinous fuel subsidies and to boost education.

The big worry about Jokowi is that he might be out of his depth in high politics. That is partly because he lacks experience: his views on foreign policy are still barely known. His campaign was amateurish, relying mainly on the perhaps, naive assumption, that honesty and an impressive record would be good enough. It turns out that Jokowi was right; Indonesians did not buy the slick, orchestrated campaign of General Prabowo. Jokowi is a man of the streets and neighborhoods, whereas past Indonesian leaders have ruled from on high. He has no ties to the Suharto regime, unlike most of his predecessors, and that represents a clean break.

Jokowi has been underestimated before. Indonesia faces a geopolitical challenges with China over its Natuna islands in the South China Sea along with its ASEAN leadership demands and international economic challenges. Standing still will not be the easiest option. Indeed, his capacity to attract powerful technocratic advice could see Jokowi pursue a more proactive and internationalist agenda than his predecessors.

Jokowi’s endearing trait—his humility—turned into a liability during the campaign as his image as an outsider was compromised by his reliance on his party’s grande dame, Megawati Sukarnoputri, the daughter of modern Indonesia’s founder and a former President herself. She has appeared on occasion to be grudging in her support for Jokowi. This reliance is likely to fade in time as Jokowi makes his own mark.

There is a leadership trait which Jokowi possesses which is both visionary and courageous. As the world’s 4th largest country, and a Muslim-majority one at that, the ethnic Chinese have been the political scapegoats forever. During the Suharto years, a drive through Jakarta’s Chinatown, Kota, was remarkable for its lack of Chinese characters, symbols, architecture and even names in English—the ethnic Chinese were literally hidden from view. The bloody anti-Chinese riots (which General Prabowo is said to have encouraged) in Kota and elsewhere left deep cultural wounds. Jokowi is the first Indonesian politician to actively begin the healing process. When he ran for the Governorship of Jakarta, Jokowi had the courage to have an ethnic Chinese, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) as his successful running mate. That was a historic first for Indonesia and it bodes well for Jokowi’s reputation as a cultural healer, a nation-builder, and a diplomat. Interestingly, Ahok now succeeds Jokowi as the Governor of Jakarta.

In the end, Indonesians, made the right choice. Jokowi will be a disruptive figure in in that he will have to learn to work with, and begin to breakup, the old political oligarchy, upgrade the bureaucracy, work the corruption problem, develop civilian control of the military, and continue to strengthen this fledgling democracy.

This is Indonesia’s “John Adams Moment.”

(David Day is the Chairman of the Board of the Hawaii Indonesia Chamber of Commerce and an international business lawyer).