In the wake of the state funeral for Vietnam’s legendary General Vo Nguyen Giap, we thought it appropriate to share with you some heartbreaker photos taken in August of 1945 in the mountains outside of Hanoi. They are heartbreakers only if you recognize what could have been, instead of the carnage that followed.

We do not ascribe blame for the failure to build on this relationship but only want to point out that it did not happen and perhaps, could have.

August, 1945

Pac Bo, Vietnam

In the photo above, American OSS (Predecessor to the CIA) “Deer Team” members pose with (then) Viet Minh leaders Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap during a military training at Tan Trao, in the mountains north of Hanoi in August, 1945. Deer Team members standing, l to r, are Rene Defourneaux, (Ho Chi Minh), Allison Thomas, (Vo Nguyen Giap), Henry Prunier and Paul Hoagland, far right. Kneeling, left, are Lawrence Vogt and Aaron Squires. (Rene Defourneaux).

1945

Toward the end of World War II, the U.S. Office of Special Operations (the OSS), the precursor to the CIA, started doing business with the communist-dominated Viet Minh, led by the ascetic and mysterious globe trotter Ho Chi Minh. The aim was to use the Viet Minh to drive the Japanese out of what had been French Indochina. But events were moving way too fast for coherent American policy to be made.

In return for the Viet Minh’s help against the Japanese, the OSS provided the Communist-dominated group with weapons, radio sets, medicines and training. The two groups quickly became very friendly and fought as comrades-in-arms in capturing the Japanese garrison at Tan Trao. They celebrated by getting drunk together. Along the way there would be such incongruous (in retrospect) actions as an OSS medic saving the life of the very sick Ho Chi Minh.

The Japanese, traumatized by Hiroshima and Nagasaki, surrendered much earlier than expected. Ho’s forces declared independence the very same day that General MacArthur accepted the formal Japanese surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri, September 2, 1945. In so doing, Ho’s Viet Minh looked to America for friendship and even included some phrasing from the American Declaration of Independence in their own, with Ho carefully checking the words of Thomas Jefferson with his OSS colleagues by radiophone from a shophouse in Hanoi’s Old Quarter as it was being drafted.

The Vietnamese Declaration of Independence that Ho Chi Minh drafted begins:

“To the compatriots of the entire country,

All men are created equal; they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights; among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. This immortal statement was made in the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America in 1776. In a broader sense, this means: All the peoples on the earth are equal from birth, all the peoples have a right to live, to be happy and free…”

Ba Dinh Square, Hanoi

Ho was clearly influenced by the political writings and values of the American Founders. Up on the stage at Ba Dinh Square in Hanoi, clear for all to see, OSS Major Archimedes Patti stood behind Ho. There are photos of Patti saluting the Vietnamese flag as the band played the Vietnamese and the US national anthems. Then, coincidentally, a clearly-marked U.S. plane flew over Ba Dinh Square during the ceremony. Was it by accident or design? It remains a mystery. Either way, it was apparent to everyone in the square that day that Ho Chi Minh (and Vo Nguyen Giap) had powerful backers and that the forces of Ho Chi Minh were clearly the political and spiritual leader of the Vietnamese revolution against the country’s French overlords.

Meanwhile, Chiang Kai-Shek’s undisciplined and rapacious troops, defeated Japanese forces, some French military people and colons and a few bemused Americans all milled around in Hanoi waiting for resolution of the dangerous and confused situation in which Indochina found itself at the end of World War II.

The U.S. adventure in Hanoi ended quickly, and it swiftly became clear that the French would fight to regain their lucrative colonies in Indochina. After all, because the mother country was, at the time, reduced to rubble–it was critical for France that she quickly re-open her colonial cash pipeline from Vietnam in the rubber, tin and other profitable Vietnamese exports of that era.

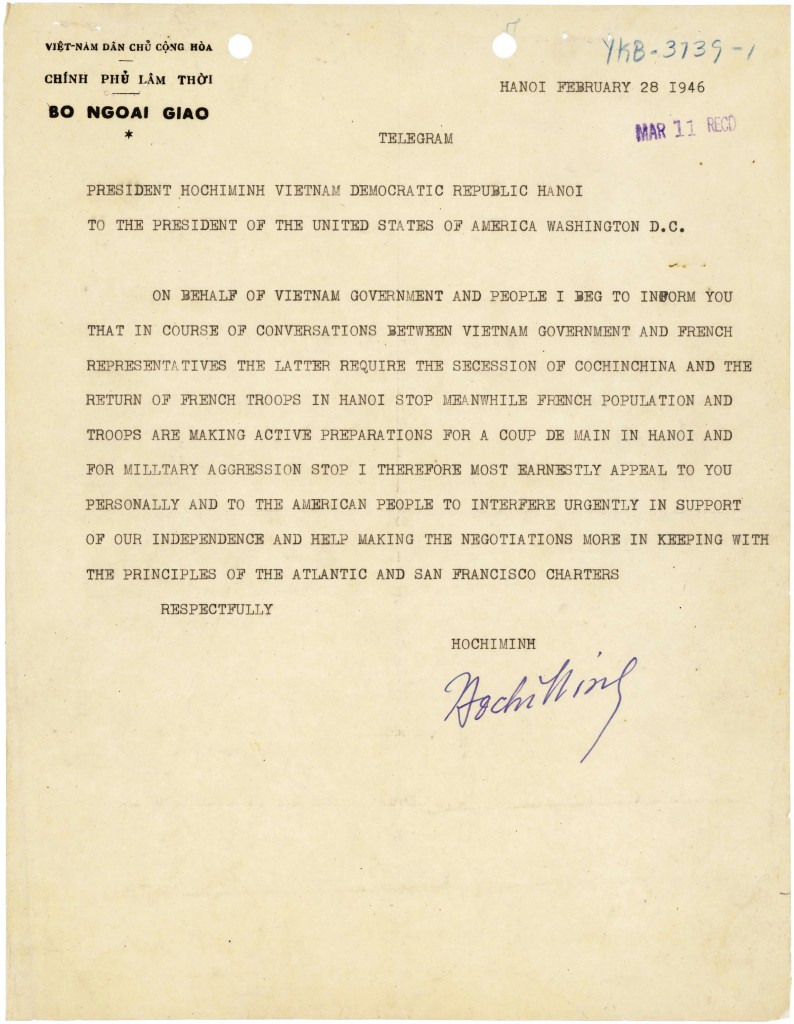

Following the Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945, the French began to return to Hanoi and Saigon and made it clear that they had no intention of abandoning the colony. In an effort to block the French return, Ho Chi Minh sent several telegrams to Washington seeking assistance against the French. These telegrams were written by Ho personally, and typed on his own typewriter. The telegrams were addressed to President Truman, sent via the State Department, but, oddly, never delivered to Truman. Here is one of several Ho sent in 1946:

February 1946

At the same time, bewildered U.S. policy makers in the inexperienced Truman administration were dealing with domestic pressures to send U.S. forces home and anxiety about upsetting the French. While the precise point at which the Truman Administration turned its back on Vietnam is unclear, we do know that France was desperate to re-start its colonial cash flow and de Gaulle, always playing hard to get, was dragging his feet during the negotiations on French participation in the precursor to NATO, the Western Union, initiated formally in 1948.

President Truman did not share Roosevelt’s strong democratic principles. He was more concerned with keeping the French happy as a major business and security partner, as well as helping stand that country back upon its feet again. Plus, there was already on the horizon the “Great Imagined Fear” of the Russians, and de Gaulle knew how to play his cards just right. De Gaulle, in mid-march 1945, had already said in discussion with the (then) Roosevelt administration:

“What are you driving at? Do you want us to become, for example, one of the federated states under the Russian aegis? The Russians are advancing apace as you well know. When Germany falls they will be upon us. If the public here comes to realize that you are against us in Indochina there will be terrific disappointment and nobody knows to what that will lead. We do not want to become Communist; we do not want to fall into the Russian orbit, but I hope that you will not push us into it.”

[by, say, letting the Vietnamese have democratic control over their own country].

Truman and the U.S. State Department made no response to Ho Chi Minh’s numerous telegrams seeking assistance against the French. Washington feared that in the chaos and economic distress of immediate post-war France that the communists would take power there. So it pulled back from what had seemed to have been its support for Vietnamese nationalism under the Viet Minh and began to support the French.

The die was cast for a future conflict and, as Minister of Defense during the Vietnam War, Vo Nguyen Giap, would play a crucial role against his old comrades from the United States.

_______________

To learn a little more about this history, check out the following articles: